IELTS Academic Reading Test

Tips and Tricks for different question types & Answers Sheet IN End of Page

Practice Test

Section 1

Instructions to follow

- You should spend 20 minutes on Questions 1-13 which are based on Reading

Passage 1

Painters of time

The world’s fascination with the mystique of Australian Aboriginal art.’

Emmanuel de Roux

A. The works of Aboriginal artists are now much in demand throughout the world, and not just in Australia, where they are already fully recognised: the National Museum of Australia, which opened in Canberra in 2001, designated 40% of its exhibition space to works by Aborigines. In Europe their art is being exhibited at a museum in Lyon. France, while the future Quai Branly museum in Paris which will be devoted to arts and civilisations of Africa. Asia, Oceania and the Americas plans to commission frescoes by artists from Australia.

B. B. Their artistic movement began about 30 years ago. But its roots go back to time immemorial. All the works refer to the founding myth of the Aboriginal culture, ‘the Dreaming’. That internal geography, which is rendered with a brush and colours, is also the expression of the Aborigines’ long quest to regain the land which was stolen from them when Europeans arrived in the nineteenth century. ‘Painting is nothing without history.’ says one such artist- Michael Nelson Tjakamarra.

C. There are now fewer than 400,000 Aborigines living in Australia. They have been swamped by the country’s 17.5 million immigrants. These original ‘natives’ have been living in Australia for 50,000 years, but they were undoubtedly maltreated by the newcomers. Driven back to the most barren lands or crammed into slums on the outskirts of cities, the Aborigines were subjected to a policy of ‘assimilation’, which involved kidnapping children to make them better ‘integrated’ into European society, and herding the nomadic Aborigines by force into settled communities.

D. It was in one such community, Papunya, near Alice Springs, in the central desert, that Aboriginal painting first came into its own. In 1971, a white school teacher. Geoffrey Bardon, suggested to a group of Aborigines that they should decorate the school walls with ritual motifs, so as to pass on to the younger generation the myths that were starting to fade from their collective memory. Lie gave them brushes, colours and surfaces to paint on cardboard and canvases. He was astounded by the result. But their art did not come like a bolt from the blue: for thousands of years Aborigines had been ‘painting’ on the ground using sands of different colours, and on rock faces. They had also been decorating their bodies for ceremonial purposes. So there existed a formal vocabulary.

E. This had already been noted by Europeans. In the early twentieth century, Aboriginal communities brought together by missionaries in northern Australia had been encouraged to reproduce on tree bark the motifs found on rock faces. Artists turned out a steady stream of works, supported by the churches, which helped to sell them to the public, and between 1950 and I960 Aboriginal paintings began to reach overseas museums. Painting on bark persisted in the north, whereas the communities in the central desert increasingly used acrylic paint, and elsewhere in Western Australia women explored the possibilities of wax painting and dyeing processes, known as ‘batik’.

F. What Aborigines depict are always elements of the Dreaming, the collective history that each community is both part of and guardian of. I Dreaming is the story of their origins, of their ‘Great Ancestors’, who passed on their knowledge, their art and their skills (hunting, medicine, painting, music and dance) to man. ‘The Dreaming is not synonymous with the moment when the world was created.’ says Stephane Jacob, one of the organisers of the Lyon exhibition. ‘For Aborigines, that moment has never ceased to exist. It is perpetuated by the cycle of the seasons and the religious ceremonies which the Aborigines organise. Indeed the aim of those ceremonies is also to ensure the permanence of that golden age. The central function of Aboriginal painting, even in its contemporary manifestations, is to guarantee the survival of this world. The Dreaming is both past, present and future.

G. Each work is created individually, with a form peculiar to each artist, but it is created within and on behalf of a community who must approve it. An artist cannot use a ‘dream’ that does not belong to his or her community, since each community is the owner of its dreams, just as it is anchored to a territory marked out by its ancestors, so each painting can be interpreted as a kind of spiritual road map for that community.

H. Nowadays, each community is organised as a cooperative and draws on the services of an art adviser, a government-employed agent who provides the artists with materials, deals with galleries and museums and redistributes the proceeds from sales among the artists.

I. Today, Aboriginal painting has become a great success. Some works sell for more than $25,000, and exceptional items may fetch as much as $180,000 in Australia. By exporting their paintings as though they were surfaces of their territory, by accompanying them to the temples of western art the Aborigines have redrawn the map of their country, into whose depths they were exiled,* says Yves Le Fur of the Quai Branly museum. ‘Masterpieces have been created. Their undeniable power prompts a dialogue that has proved all too rare in the history of contacts between the two cultures’.

Questions 1-8

Instructions to follow

- The reading Passage has nine paragraphs A-I

- Choose the most suitable heading for paragraphs A-F from the list of headings below.

- Write the correct number (i-viii) in boxes 1-8 on your answer sheet.

List of Headings

- Amazing results from a project

- New religious ceremonies

- Community art centres

- Early painting techniques and marketing systems

- Mythology and history combined

- The increasing acclaim for Aboriginal art

- Belief in continuity

- Oppression of a minority people

Paragraph A

Paragraph B

Paragraph C

Paragraph D

Paragraph E

Paragraph F

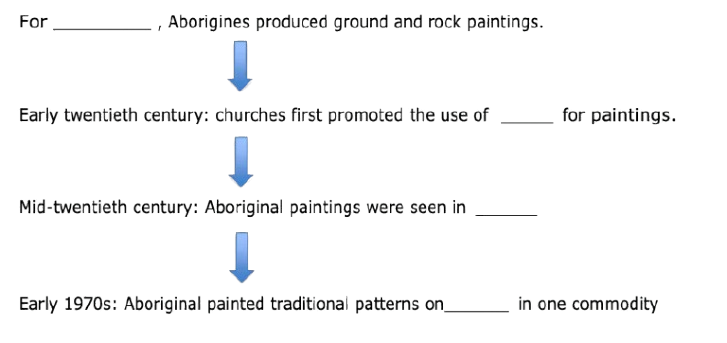

Questions 7-10

Instructions to follow

- Complete the flowchart below

- Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer

- Write your answer in boxes 7-10 from the passage for each answer.

Questions 11-13

Instructions to follow

- Choose the correct answer, A, B, C or D

- Write your answers in boxes 11-13 on your answer sheet

11. In Paragraph G, the writer suggests that an important feature of Aboriginal art is

A. its historical context.

B. its significance to the group.

C. its religious content.

D. its message about the environment.

12. In Aboriginal beliefs, there is a significant relationship between

A. communities and lifestyles.

B. images and techniques

C. culture and form.

D. ancestors and territory.

13. In Paragraph I. the writer suggests that Aboriginal art invites Westerners to engage with

A. The Australian land.

B. their own art.

C. Aboriginal culture.

D. their own history.

Section 2

Instructions to follow

- You should spend 20 minutes on Questions 14-26 which are based on Reading

Passage 2

Ancient Storytelling

A. It was told, we suppose, to people crouched around a fire: a tale of adventure, most likely- relating some close encounter with death; a remarkable hunt, an escape from mortal danger; a vision, or something else out of the ordinary. Whatever its thread, the weaving of this story was done with a prime purpose. The listeners must keep listening. They must not fall asleep. So, as the story went on, its audience should be sustained by one question above all. What happens next?

B. The first fireside stories in human history can never be known. They were kept in the heads of those who told them. This method of storage is not necessarily inefficient. From documented oral traditions in Australia, the Balkans and other parts of the world we know that specialised storytellers and poets can recite from memory literally thousands of lines, in verse or prose, verbatim-word for word. But while memory is rightly considered an art in itself, it is clear that a primary purpose of making symbols is to have a system of reminders or mnemonic cues – signs that assist us to recall certain information in the mind’s eye.

C. In some Polynesian communities, a notched memory stick may help to guide a storyteller through successive stages of recitation. But in other parts of the world, the activity of storytelling historically resulted in the development or even the invention of writing systems. One theory about the arrival of literacy in ancient Greece, for example, argues that the epic tales about the Trojan War and the wanderings of Odysseus – traditionally attributed to Homer – were just so enchanting to hear that they had to be preserved. So the Greeks, c.750-700 BC, borrowed an alphabet

from their neighbors in the eastern Mediterranean, the Phoenicians.

D. The custom of recording stories on parchment and other materials can be traced in many manifestations around the world, from the priestly papyrus archives of

ancient Egypt to the birch-bark scrolls on which the North American Ojibway Indians set down their creation-myth. It is a well-tried and universal practice: so much so that to this day storytime is probably most often associated with words on paper. The formal practice of narrating a story aloud would seem-so we assume-to have given way to newspapers, novels and comic strips. This, however, is not the case. Statistically, it is doubtful that the majority of humans currently rely upon the written word to get access to stories. So what is the alternative source?

E.Each year, over 7 billion people will go to watch the latest offering from Hollywood, Bollywood and beyond. The supreme storyteller of today is cinema. The movies, as distinct from still photography, seem to be an essential modem phenomenon. This is an illusion, for there are, as we shall see, certain ways in which the medium of film is indebted to very old precedents

of arranging ‘sequences’ of images. But any account of visual storytelling must be with the recognition that all storytelling beats with a deeply atavistic pulse: that is, a ‘good story’ relies upon formal patterns of plot and characterisation that have been embedded in the practice of storytelling over many generations.

F. Thousands of scripts arrive every week at the offices of the major film studios. But aspiring screenwriters really need to look no further for essential advice than the fourth- century BC Greek Philosopher Aristotle. He left some incomplete lecture notes on the art of telling stories in various literary and dramatic modes, a slim volume known as The Poetics. Though he can never have envisaged the popcorn-fuelled actuality of a multiplex cinema, Aristotle is almost prescient about the key elements required to get the crowds flocking to such a cultural hub. He analyzed the process with cool rationalism. When a story enchants us, we lose the sense of where we are; we are drawn into the story so thoroughly that we forget it is a story being told. This is, in Aristotle’s

phrase, ‘the suspension of disbelief.

G. We know the feeling. If ever we have stayed in our seats, stunned with grief, as the credits roll by, or for days after seeing that vivid evocation of horror have been nervous about taking a shower at home, then we have suspended disbelief. We have been caught, or captivated, in the storyteller’s web. Did it all really happen? We really thought so-for a while. Aristotle must have witnessed often enough this suspension of disbelief. He taught at Athens, the city where theater developed as a primary form of civic ritual and recreation. Two theatrical types of storytelling, tragedy and comedy, caused Athenian audiences to lose themselves in sadness and laughter respectively. Tragedy, for Aristotle, was particularly potent in its capacity to enlist and then purge the emotions of those watching the story unfold on the stage, so he tried to identify those factors in the storyteller’s art that brought about such engagement. He had, as an obvious sample for analysis, not only the fifth-century BC masterpieces of Classical Greek tragedy written by Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides. Beyond them stood Homer, whose stories even then had canonical status: The Iliad and The Odyssey were already considered literary landmarks-stories by which all other stories should be measured. So what was the secret of Homer’s narrative art?

H. It was not hard to find. Homer created credible heroes. His heroes belonged to the past, they were mighty and magnificent, yet they were not, in the end, fantasy figures. He made his heroes sulk, bicker, cheat and cry. They were, in short, characters – protagonists of a story that an audience would care about, would want to follow, would want to know what happens next. As Aristotle saw, the hero who shows a human side-some flaw or weakness to which mortals are prone-is intrinsically dramatic.d by logging.

Questions 1-8

Instructions to follow

- The reading Passage has nine paragraphs A-I

- Choose the most suitable heading for paragraphs A-F from the list of headings below.

- Write the correct number (i-viii) in boxes 1-8 on your answer sheet.

List of Headings

- Amazing results from a project

- New religious ceremonies

- Community art centres

- Early painting techniques and marketing systems

- Mythology and history combined

- The increasing acclaim for Aboriginal art

- Belief in continuity

- Oppression of a minority people

Paragraph A

Paragraph B

Paragraph C

Paragraph D

Paragraph E

Paragraph F

Questions 7-10

Instructions to follow

- Complete the flowchart below

- Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer

- Write your answer in boxes 7-10 from the passage for each answer.

Painters of time

The world’s fascination with the mystique of Australian Aboriginal art.’

Emmanuel de Roux

A. The works of Aboriginal artists are now much in demand throughout the world, and not just in Australia, where they are already fully recognised: the National Museum of Australia, which opened in Canberra in 2001, designated 40% of its exhibition space to works by Aborigines. In Europe their art is being exhibited at a museum in Lyon. France, while the future Quai Branly museum in Paris which will be devoted to arts and civilisations of Africa. Asia, Oceania and the Americas plans to commission frescoes by artists from Australia.

B. B. Their artistic movement began about 30 years ago. But its roots go back to time immemorial. All the works refer to the founding myth of the Aboriginal culture, ‘the Dreaming’. That internal geography, which is rendered with a brush and colours, is also the expression of the Aborigines’ long quest to regain the land which was stolen from them when Europeans arrived in the nineteenth century. ‘Painting is nothing without history.’ says one such artist- Michael Nelson Tjakamarra.

C. There are now fewer than 400,000 Aborigines living in Australia. They have been swamped by the country’s 17.5 million immigrants. These original ‘natives’ have been living in Australia for 50,000 years, but they were undoubtedly maltreated by the newcomers. Driven back to the most barren lands or crammed into slums on the outskirts of cities, the Aborigines were subjected to a policy of ‘assimilation’, which involved kidnapping children to make them better ‘integrated’ into European society, and herding the nomadic Aborigines by force into settled communities.

D. It was in one such community, Papunya, near Alice Springs, in the central desert, that Aboriginal painting first came into its own. In 1971, a white school teacher. Geoffrey Bardon, suggested to a group of Aborigines that they should decorate the school walls with ritual motifs, so as to pass on to the younger generation the myths that were starting to fade from their collective memory. Lie gave them brushes, colours and surfaces to paint on cardboard and canvases. He was astounded by the result. But their art did not come like a bolt from the blue: for thousands of years Aborigines had been ‘painting’ on the ground using sands of different colours, and on rock faces. They had also been decorating their bodies for ceremonial purposes. So there existed a formal vocabulary.

E. This had already been noted by Europeans. In the early twentieth century, Aboriginal communities brought together by missionaries in northern Australia had been encouraged to reproduce on tree bark the motifs found on rock faces. Artists turned out a steady stream of works, supported by the churches, which helped to sell them to the public, and between 1950 and I960 Aboriginal paintings began to reach overseas museums. Painting on bark persisted in the north, whereas the communities in the central desert increasingly used acrylic paint, and elsewhere in Western Australia women explored the possibilities of wax painting and dyeing processes, known as ‘batik’.

F. What Aborigines depict are always elements of the Dreaming, the collective history that each community is both part of and guardian of. I Dreaming is the story of their origins, of their ‘Great Ancestors’, who passed on their knowledge, their art and their skills (hunting, medicine, painting, music and dance) to man. ‘The Dreaming is not synonymous with the moment when the world was created.’ says Stephane Jacob, one of the organisers of the Lyon exhibition. ‘For Aborigines, that moment has never ceased to exist. It is perpetuated by the cycle of the seasons and the religious ceremonies which the Aborigines organise. Indeed the aim of those ceremonies is also to ensure the permanence of that golden age. The central function of Aboriginal painting, even in its contemporary manifestations, is to guarantee the survival of this world. The Dreaming is both past, present and future.

G. Each work is created individually, with a form peculiar to each artist, but it is created within and on behalf of a community who must approve it. An artist cannot use a ‘dream’ that does not belong to his or her community, since each community is the owner of its dreams, just as it is anchored to a territory marked out by its ancestors, so each painting can be interpreted as a kind of spiritual road map for that community.

H. Nowadays, each community is organised as a cooperative and draws on the services of an art adviser, a government-employed agent who provides the artists with materials, deals with galleries and museums and redistributes the proceeds from sales among the artists.

I. Today, Aboriginal painting has become a great success. Some works sell for more than $25,000, and exceptional items may fetch as much as $180,000 in Australia. By exporting their paintings as though they were surfaces of their territory, by accompanying them to the temples of western art the Aborigines have redrawn the map of their country, into whose depths they were exiled,* says Yves Le Fur of the Quai Branly museum. ‘Masterpieces have been created. Their undeniable power prompts a dialogue that has proved all too rare in the history of contacts between the two cultures’.

Questions 14-18

Instructions to follow

- The Reading passage has eight paragraph A-H.

- Which paragraph contains the following information ?

14. A misunderstanding of a modern way for telling

15. The typical forms mentioned for telling stories

16.The fundamental aim of storytelling

17. A description of reciting stories without any

18. assistance How to make story characters Attractive

Questions 19-22

Instructions to follow

- Classify the following information as referring to

A. adopted the writing system from another country

B. used organic materials to record stories

C. used tools to help to tell stories

19. Egyptians

20. Ojibway

21. Polynesians

22. Greek

Questions 23-36

Instructions to follow

- Complete the sentences below with ONE WORD ONLY from the passage.

23. Aristotle wrote a book on the art of storytelling called

24. Aristotle believed the most powerful type of story to move

25. listeners is Aristotle viewed Homer’s works as

26. Aristotle believed attractive heroes should have some

Section 3

Instructions to follow

- You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 27-40 which are based on Reading Passage 3

Musical Maladies

Norman M. Weinberger reviews the latest work of Oliver Sacks on music.

Music and the brain are both endlessly fascinating subjects, and as a neuroscientist specialising in auditory learning and memory, I find them especially intriguing. So I had high expectations of Musicophilia, the latest offering from neurologist and prolific author Oliver Sacks. And I confess to feeling a little guilty reporting that my reactions to the book are mixed

Sacks himself is the best part of Musicophilia. He richly documents his own life in the book and reveals highly personal experiences. The photograph of him on the cover of the book— which shows him wearing headphones, eyes closed, clearly enchanted as he listens to Alfred Brendel perform Beethoven’s Pathétique Sonata—makes a positive impression that is borne out by the contents of the book. Sacks’s voice throughout is steady and erudite but never pontifical. He is neither self-conscious nor self-promoting.

The preface gives a good idea of what the book will deliver. In it Sacks explains that he wants to convey the insights gleaned from the “enormous and rapidly growing body of work on the neural underpinnings of musical perception and imagery, and the complex and often bizarre disorders to which these are prone ” He also stresses the importance of “the simple art of observation” and “the richness of the human context.” He wants to combine “observation and description with the latest in technology,” he says, and to imaginatively enter into the experience of his patients and subjects. The reader can see that Sacks, who has been practicing neurology for 40 years, is torn between the “old- fashioned” path of observation and the new-fangled, high-tech approach: He knows that he needs to take heed of the latter, but his heart lies with the former.

The book consists mainly of detailed descriptions of cases, most of them involving patients whom Sacks has seen in his practice. Brief discussions of contemporary neuroscientific reports are sprinkled liberally throughout the text. Part I, “Haunted by Music,” begins with the strange case of Tony Cicoria, a nonmusical, middle-aged surgeon who was consumed by a love of music after being hit by lightning. He suddenly began to crave listening to piano music, which he had never cared for in the past. He started to play the piano and then to compose music, which arose spontaneously in his mind in a “torrent” of notes. How could this happen? Was the cause psychological? (He had had a near-death experience when the lightning struck him.) Or was it the direct result of a change in the auditory regions of his cerebral cortex? Electro-encephalography (EEG) showed his brain waves to be normal in the mid-1990s, just after his trauma and subsequent “conversion” to music. There are now more sensitive tests, but Cicoria has declined to undergo them; he does not want to delve into the causes of his musicality. What a shame!

Part II, “A Range of Musicality,” covers a wider variety of topics, but unfortunately, some of the chapters offer little or nothing that is new. For example, chapter 13, which is five pages long, merely notes that the blind often have better hearing than the sighted. The most interesting chapters are those that present the strangest cases. Chapter 8 is about “amusia,” an inability to hear sounds as music, and “dysharmonia,” a highly specific IELTSMockPractice.com 27 impairment of the ability to hear harmony, with the ability to understand melody left intact. Such specific “dissociations” are found throughout the cases Sacks recounts.

To Sacks’s credit, part III, “Memory, Movement and Music,” brings us into the underappreciated realm of music therapy. Chapter 16 explains how “melodic intonation therapy” is being used to help expressive aphasia patients (those unable to express their thoughts verbally following a stroke or other cerebral incident) once again become capable of fluent speech. In chapter 20, Sacks demonstrates the near-miraculous power of music to animate Parkinson’s patients and other people with severe movement disorders, even those who are frozen into odd postures. Scientists cannot yet explain how music achieves this effect.

To readers who are unfamiliar with neuroscience and music behavior, Musicophilia may be something of a revelation. But the book will not satisfy those seeking the causes and implications of the phenomena Sacks describes. For one thing, Sacks appears to be more at ease discussing patients than discussing experiments. And he tends to be rather uncritical in accepting scientific findings and theories.

It’s true that the causes of music-brain oddities remain poorly understood. However, Sacks could have done more to draw out some of the implications of the careful observations that he and other neurologists have made and of the treatments that have been successful. For example, he might have noted that the many specific dissociations among components of music comprehension, such as loss of the ability to perceive harmony but not melody, indicate that there is no music center in the brain. Because many people who read the book are likely to believe in the brain localisation of all mental functions, this was a missed educational opportunity.

Another conclusion one could draw is that there seem to be no “cures” for neurological problems involving music. A drug can alleviate a symptom in one patient and aggravate it in another, or can have both positive and negative effects in the same patient. Treatments mentioned seem to be almost exclusively antiepileptic medications, which “damp down” the excitability of the brain in general; their effectiveness varies widely.

Finally, in many of the cases described here the patient with music-brain symptoms is reported to have “normal” EEG results. Although Sacks recognizes the existence of new technologies, among them far more sensitive ways to analyze brain waves than the standard neurological EEG test, he doesn’t call for their use. In fact, although he exhibits the greatest com-passion for patients,

he conveys no sense of urgency about the pursuit of new avenues in the diagnosis and treatment of music-brain disorders. This absence echoes the hook’s preface, in which Sacks expresses fear that “the simple art of observation may be lost” if we rely too much on new technologies. He does call for both approaches, though, and we can only hope that the neurological community will respond.

Questions 27-30

Instructions to follow

- Choose the correct letter A, B, C or D.

- Write the correct letter in boxes 27-30 on your answer sheet.

27. Why does the writer have mixed feelings about the book?

A. The guilty feeling made him so.

B. The writer expected it to be better than it was.

C. Sacks failed to include his personal stories in the book.

D. This is the only book written by Sacks.

28. What is the best part of the book?

A. the photo of Sacks listening to music

B. the tone of voice of the

C. the autobiographical description in the book

D. the description of Sacks’s wealth

29. In the preface, what did Sacks try to achieve?

A. make terms with the new

B. give detailed description of various musical disorders

C. explain how people understand music

D. explain why he needs to do away with simple observation

30. What is disappointing about Tony Cicoria’s case?

A. He refuses to have further tests.

B. He can’t determine the cause of his sudden musicality.

C. He nearly died because of the lightning.

D. His brain waves were too normal to show anything.

Questions 31-36

Instructions to follow

- Do the following statements agree with the views of the writer in Reading Passage 3?

- In boxes 31-36 on your answer sheet, write

YES If the statement agrees with the views of the

writer NO If the statement contradicts the views of the

writer NOT GIVEN If it impossible to say what the writer

31. It is difficult to give a well-reputable writer a less than favorable review.

32. Beethoven’s Pathétique Sonata is a good treatment for musical disorders.

33. Sacks believes technological methods are not important compared with

observation when studying his patients.

34. It is difficult to understand why music therapy is undervalued.

35. Sacks should have more skepticism about other theories and findings.

36. A sack is impatient to use new testing methods.

Questions 37-40

Instructions to follow

- Complete each sentence with the correct ending, A-F, below.

- Write the correct letter, A-F, in boxes 37-40 on your answer sheet.

37. The dissociations between harmony and melody

38. The study of treating musical disorders

39. The EEG scans of Sacks’s patients

40.Sacks believes testing based on new technology

A. Show no music-brain disorders

B. Indicates that medication can have varied results

C. Is key for the neurological community to unravel the mysteries.

D. Should not be used in isolation.

E. Indicate that not everyone can receive good education.

F. Show that music is not localised in the brain.

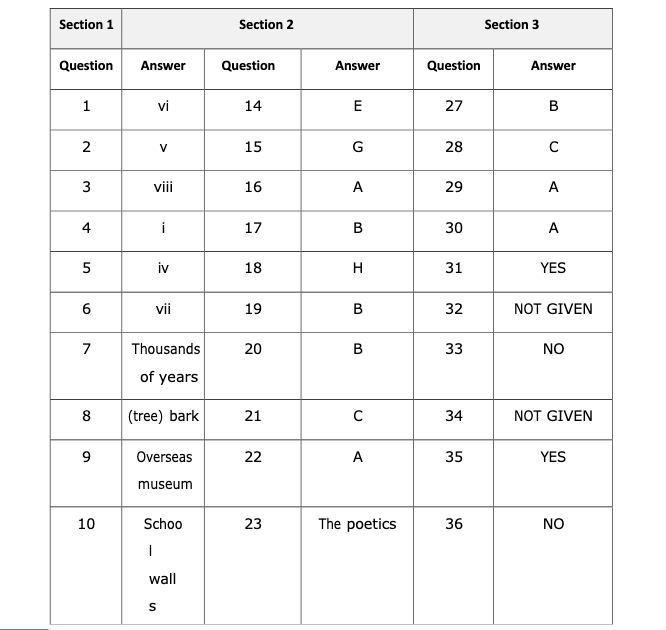

Answer Keys – Reading Test 1